Feb 23 2010

More Information About Cards than You’ll Ever Need to Know

written by: John under Card Games Comments: Comments Off

While at least 80% of Americans, and probably about the same percentage of other countries use playing cards on a regular basis, or at least have a deck or two in their homes, but this staple of our global culture is more than just a means to a game. What follows is more information than you’ll ever need to know about cards, but those who love to play card games will appreciate it.

HISTORY OF THE CARD

Playing cards date back to somewhere between 800 AD and 1100 AD. An ancient Chinese dictionary references cards and claims they originated during the reign of Emporer Seun-Ho around 1120. As legend goes, Seun-Ho used them to amuse and entertain himself and the people he lived with. In India and Egypt they were used for fortune telling.

Despite our lack of knowledge concerning exactly how playing card came to Europe, what is generally accepted is that in the late 1300s, the Mamelukes of Egypt introduced their style of cards to Europe. A pack of Mameluke cards consisted of four “suits,” each of which contained 13 cards, just like modern day playing cards. These suits were called cups, swords, coins, and polo sticks. Each suit consisted of 10 numbered cards and three court cards, the King, the Vice-King, and the Second Vice-King.

The earliest references to cards in Europe are mostly from French literature. The diaries of King Charles VI note that he bought three packs of cards in 1392. King Charles VI’s cards were hand-painted by an artist and used for “diversion.” These original cards featured four suits as well, though the names had by altered a bit (cups, swords, coins, and batons), and one additional card had been added to each suit, making 14 cards per suit. The added card was called the “Cavalier” or “Mounted Valet” and served as the lowest of four court cards. Europeans adopted a wide range of different suits and styles according to local tastes and the preferences of the artists who created the decks. Sometimes even five suits were included. Decks that featured the four suits we know today, spades, diamonds, hearts, and clubs (also referred to as clovers) first appeared in France in the late 1400s.

Over the years, various scholars have put forth the notion that the four suits in a deck of playing cards were intended to represent the four classes of medieval society. The spades were said to have represented the aristocracy (as spearheads, the weapons of the knights), hearts stood for the Church, diamonds were a sign of wealth (from the paving stones used in chancels of churches, where the well-to-do were buried, and the clover (the food of swine) denoted the peasant class.

It was also around this time that the French card masters started the practice of assigning identities to the kings on their cards. The King of Hearts was Charlemagne (Charles the Great); the King of Diamonds was Julius Caesar; the King of Clubs was Alexander the Great; and the King of Spades was King David from the Holy Bible.

The Germans also played a pivotal role in the popularity of card games when they started to print packs in volume quantities around 1418. In Germany the most usual suit combination came to be the following rustic designs: hearts, bells, leaves, and acorns. Because they began to export their relatively cheap decks of cards to other European countries, the German influence in card design was probably the largest. So another far more likely theory for the evolution of the four suits we use today is that the French just based their cards on the German images, the leaves transposing to spades, the acorn to clubs, and the bells to diamonds.

Though specific design elements of the court cards are rarely used in game play and many differ between designs, a few are notable. The Jack of Spades, Jack of Hearts, and King of Diamonds are drawn in profile, while the rest of the courts are shown in full face; these cards are commonly called “one-eyed.” This is where the phrase “One-eyed Jack” comes from.

The King of Hearts is the only King without a mustache, and is also typically shown with a sword behind his head, making him appear to be stabbing himself (aka “Suicide King”). Some argue though that this king is only hiding his sword behind him. This feature, along with his missing moustache have garnered him the name, “The False King.” Another king, the King of Diamonds holds his axe behind his head with the blade facing toward him. He is traditionally armed with an axe while the other three kings are armed with swords, and thus the King of Diamonds is sometimes referred to as “The Man with the Axe.”

Another take on the deck of cards is a religious one. At a time when the Church frowned upon nearly everything that was used for entertainment purposes, cards were deemed unholy and a tool of sin. However, a piece of 19th Century British Literature, The Soldier’s Almanac, Bible, and Prayer Book, tells a different story. As the parallel goes, each component of a deck of cards can be related to something righteous:

- The Ace, one true God

- 2, the Old and New Testaments of the Bible

- 3, the Holy Trinity

- 4, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, authors of the four gospels in the Holy Bible, and four of Jesus’ disciples

- 5, two groups of five virgins

- 6, God completed Creation in six days

- 7, the Sabbath day

- 8, the eight righteous who were saved by God during the Great Flood—Noah, his wife, their three sons, and the sons’ wives

- 9, nine of 10 lepers that didn’t thank Jesus for healing them

- 10, the 10 Commandments

- King, Jesus Christ

- Queen, the Virgin Mary, Queen of Heaven

- Jack, the Devil.

And there’s even a mathematical theory to a deck of cards that directly corresponds with time and space:

- The two colors (black and red) signify night and day.

- The four suits is aligned with the four seasons.

- If you total the face values of each card in a deck, Ace counting as 1, Jack as 11, Queen as 12, and King as 13, plus 1 for the Joker, you will find that the sum equals 365, and there are 365 days in a year (the extra Joker serves as Leap Year).

- 52 cards in a deck equates to 52 weeks in a year.

- The medium number between Ace (1) and King (13) is 7: seven days in a week.

- The average value of the sum of the court cards is 12: 12 hours in a day/12 hours in a night.

- There are also 12 months in a year, and 12 face cards in a deck.

- Thirteen cards in each suit stands for the 13 trips that the moon takes around the Earth in one year. This fact leads some to believe that cards were originally developed using the lunar calendar.

- Another correlation with the number 13 is that there are 13 weeks in each quarter of a year, or 13 weeks per season, 13 cards per suit.

But there’s more… if you were to start with a 52-card deck and deal them out one by one into two piles, then place the second pile on top of the first and repeat 24 times, the deck will return to the original order in which it started (24 hours in a day).

MADE IN THE USA

Nowadays, the largest producer of playing cards in the world, the United States Playing Card Company (USPC), is located in Cincinnati, Ohio. The company was founded in 1867 and currently produces more than 100 million decks annually. The USPC manufactures such brands as Bee Playing Cards, which first originated in 1892 and Bicycle, which has been in continuous production since 1885. Playing card brands Hoyle and Aviator are also produced by USPC.

CARDS AND WAR

During World War II, the company secretly worked with the US government to fabricate special decks for American prisoners of war in Germany camps. When these cards, disguised as gifts to the prisoners were moistened, they peeled apart to reveal sections of a map that would indicate precise escape routes.

During World War II, the company secretly worked with the US government to fabricate special decks for American prisoners of war in Germany camps. When these cards, disguised as gifts to the prisoners were moistened, they peeled apart to reveal sections of a map that would indicate precise escape routes.

The Ace of Spades also served as served purpose in the Vietnam War when in February 1966, two lieutenants of Company C, Second Battalion, 35th Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, wrote the USPC company and requested decks containing nothing but the Bicycle brand Ace of Spades. They were used in psychological warfare, as the Viet Cong were very superstitious and highly frightened by this Ace. These decks were housed in plain white tuckcases, inscribed “Bicycle Secret Weapon.” The cards were deliberately scattered in the jungle and in hostile villages during raids. The very sight of the Ace caused the Viet Cong to flee.

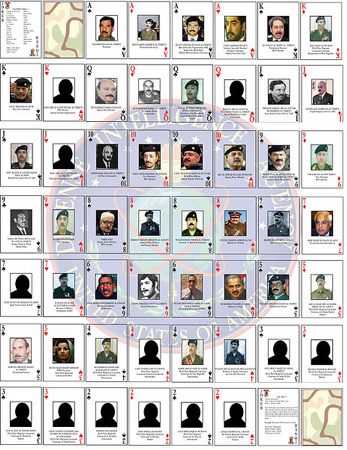

And remember the US Most Wanted Iraqi deck that identified the most wanted members of Saddam Hussein’s legion, the Baath Party, and the Revolutionary Command Council? These “personality identification playing cards” each contained the name and picture (if available), as well as the job the villain performed, ranked in appropriate order with the cards, Saddam Hussein indicated on the Ace of Spades. As troops played with the cards, it helped them to recognize the faces of the enemies, should they run into them in combat. Today, a deck of these cards serves as a reminder of the terror the US was undergoing at the time.

Through more than 600 years of creative and technical innovation, culture has left its mark on the design and manufacture of playing cards. Whether we consider them as a game or an artifact, as merchandise or something which unites people, there is a fascination and history in the imagery.

Comments Off - Click Here to Speak Up